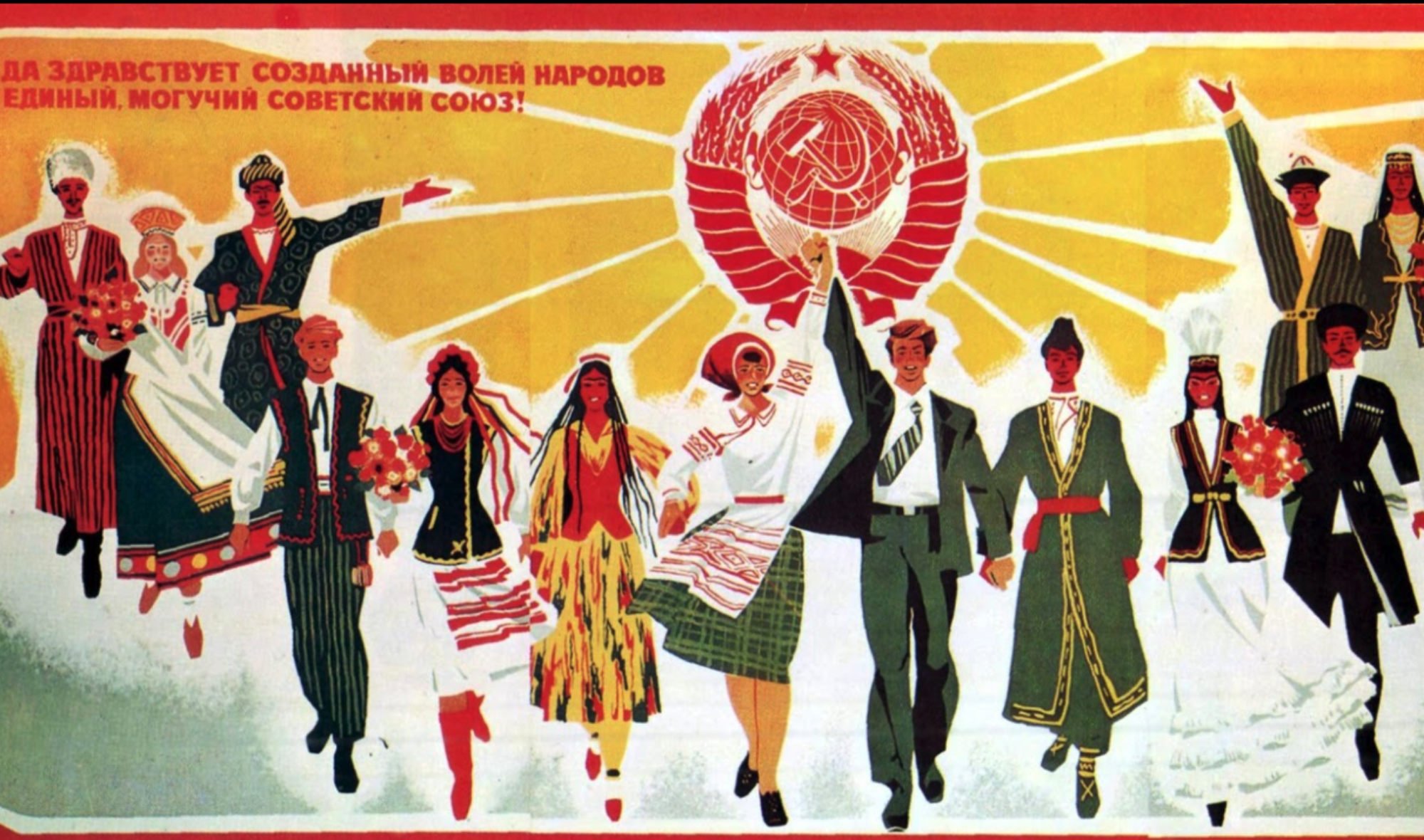

At the beginning of chapter eight Paul Stronski discusses Stalin’s death and more specifically the aftermath of his death. Citizens of Moscow were literally killing each other in order to pay their respects to their former leader. A man who is responsible for incredibly horrible acts, yet was the leader of the Soviet Union for so many years and spearheaded growth in the “nation”. He was the leader and with his death worry among the citizens of Moscow seemed to be very prevalent. However, in areas were Stalin’s body was not kept mourning seemed to be great but less dramatic than Moscow. But, mourning still seemed great and important. Thus it seems as if the mourning of Stalin was important in order for the Soviet Union to continue. So much so that it almost seems suspicious in areas where people are not “Russian”. But, many letters were written about the death of Stalin and mourning was happening. Stronski states, “Individual or institutional letters from the Uzbeck capital [in regards to Stalin’s death] most frequently were signed by people with Slavic last names or by Uzbeks who chose to write in Russian […]” (Stronski, 206). Moreover, the author makes a strong case that mourning from Uzbek citizens is real and honest. In an area that is decidedly “‘Sovietized'” do they act as a role model for how non-Russian Soviet areas should be reacting to Stalin’s death? Is it truly important for a strategic and grand mourning period of Stalin’s death to move the Soviet Union into the future? Why is it important?

Twelve Chairs

Going into watching this film, I was not sure what to expect. In the opening scene when Bender pretends to be a Soviet official to get stuff from a store clerk, I was not quite sure where this film was going to go. Would it be a movie presenting order? A drama? A comedy? And although it was the latter, I was still surprised that this sort of comedy was allowed in the Soviet Union. Twelve Chairs is a very light hearted movie, yet there seem to be some clear criticisms of the Soviet Union within the plot. Such is the fact that Ippolit Vorobyaninov is even looking for the chairs in the first place. He was essentially demoted, and this fortune could be a chance to reconcile that. Moreover, the priest seems pretty corrupt. I found it to be confusing that the Soviet Union would allow a movie to exist that seems to lampoon failings in their government. However, is that maybe the point? To poke fun at the instability after the war? As this film acts as a look back into a different time, is there seperation between this story and the 1970s?

Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge: State and Stage in Soviet Ukraine, The Literary Fair

Todays reading, seemed to follow a theme we’ve come to be familiar with in this course: creating a new society. It is very clear week after week that the Soviet officials are acting as entrepreneurs to create and market a new way of living. And no nation or group of nations can be complete without culture. Culture is such as affective way to instill pride and community within a group of peoples. Moreover, a cultured area of culture, the arts, have been used since the Paleolithic period. Just as it would be in any Soviet territory, the arts are used very tactically, as a tool. Mayhill Fowler states, “The arts were there-fore not a luxury, but rather a central component of the Soviet project. Consequently the state created, managed, and financially supported newspapers, journals, and arts institutions, all of which offered jobs for artists” (Fowler 58). The Soviet Union played patron to the arts to support artists in which ever media they create, however, it would not be the Soviet Union without some kinks due to hasty action. Moreover, it seems that a lot of artists in and coming out of the civil war were prolific in creating in a very close knit art scene, and many began to travel to the seemingly new artistic hub, Moscow. Specifically Mikhail Bulgakov lived in a new time where the arts had a significant place in society, and the government was funding their lives and careers. However, the art scene in Soviet Ukraine differed in significant ways, “First of all, many of the artists in Soviet Ukraine were also officials. As such, they invested as much in the creation of a new state as in the creation of a new culture” (Fowler 62). These two worlds of art existed at the same time and within the same “nation”, yet were influenced so differently.

- How do the signifigant differences between artists in Moscow and Ukraine change the way in which we could see their art? How do their positions before and after the war effect the art and culture of the new societies?

- Are the actions of Soviet Ukraine possibly treating to the doctrine of the Soviet Union? Does Soviet Ukraine do things better than the SU regarding cultural action and thought?

- How does the Literary Fair support or reject the new society the SU is trying to create?

- What is the significance of the close relationship the military has with the arts?

Art Forms and Gender in the Soviet Union and Turkmenistan

In the chapter of Portrait of Lenin, “Carpets and National Culture in Soviet Turkmenistan” the authors discuss the cultural and economic changes to Turkmenistan once the Soviet Union gets involved. The once practical and artful carpets made by Turkmen women are transformed into a solely artistic economic endeavor. (Something I found to be interesting compared to the very much anti-traditional art movements in the West) The Soviet Union’s signature mix of respective national newspapers and books were created. As well as an overall theme of socialist messages in said nationality’s language. Moreover, the Soviet Union reviewed areas of Turkmenistan culture that they deemed to be outdated, such as oppressive traditions towards female Turkmen. Most importantly, these nations were remade in a way that was inspired by Russian culture and society- modern and Western in some ways. The authors state, “Because Soviet nations were supposed to be modern and socialist, however, the communist leaders in Moscow took it upon themselves to decide which customs and traditions were acceptable and which were ‘backward’ and ‘exploitive’ and therefore destined for elimination” (Kivelson and NNeuberger, 182). Continually, in the “impressionist” documentary directed by Victor Turin, Turksib, the story of the Turkmenistan economy in the eyes of a Russian filmmaker is transcribed. The film chronicles cotton farmers transitioning into industrial work on a railroad.

Questions:

- Is it right or okay for one nation to eliminate aspects of another nation’s culture that the first nation deems to be oppressive towards a group of peoples? i.e. veiling and polygamy

- How are the cultural changes involving Turkmen women and their autonomy different than cultural changes done onto general areas of Turkmenistan culture? Are the actions taken by the Soviet Union towards women admirable? Or should they just stay out of all other nations’ businesses?

- What is significant about the carpets’ change from a practical and artful object to a purely artful one?

- In regards to the film, how does the filmmaker develop mood throughout the documentary?

The Forge of the Kazakh Proletariat?: Governments are Doomed to Create Their Own Enemies

In the chapter we read of A State of Nations : Empire and Nation-Making in the Age of Lenin and Stalin the author discussed the conflict between the Soviet Union and the Kazakh peoples. The forced industrialization and modernization by the Soviet Union was hard on the Kazakh people. The affirmative action program fostered discrimination. And such things like the living situation of Kazakh peoples was in most cases worse than their neighbors. “They were ordered to the back of the line, received goods after the Europeans had first choice, had to accept bread that was cut with the same knife used to cut pork fat (anathema to the Kazakhs’ religious practices), and withstood constant verbal abuse from the clerks” (Martin and Suny, 230). While we’ve seen discrimination of other nationalities within our other readings for this class, these instances seem very blatant, and almost akin to colonization. And while we all may expect this from the Soviet Union, it still seems surprising that they would put these actions in place given the nature of the birth of the Soviet Union- marginalized people standing up to “the man”. Which leads me to wonder, will all governments eventually create their demise from within their own nation? Will even the best government, with the best intentions eventually foster its own demise by putting people into the “loosing class”?

Discriminatory Nationalism

In chapter 8 of A Biography of No Place, Radical Hierarchies, Brown discusses the result of the German authorities entering the borderlands. She outlines Professor Karl Stumpp’s illustration of German peoples in the borderlands. He is pretty upset seeing how the German people are living. He states, “‘If they didn’t want to perish, they had to knuckle under and swallow the insults or go to cities and blend in, obscuring the traces of their former existence so as not to appear as German'” (Brown, 194). Thus an interesting and maddening dichotomy arises, where there are two governments doing deplorable actions against different groups of people based on ethnicity, religion, etc.- yet, Stumpp can still be disgusted by the treatment of fellow Germans in a different “nation”. Furthermore, Brown discusses how Stumpp ignores the other nationalities facing these conflicts in the USSR, and only focuses on the atrocities against Germans. Thus, it makes me wonder how both of these “nations” can exist at the same time whilst condemning the other? Moreover, Brown describes the process in which the German authorities organized the German Soviets, in a way that focuses on physical appearance and a strange

A Biography of No Place: The Numbers Don’t Lie?

Blake Aber

In A Biography of No

Nationalism: A tool for the Bourgeoisie to hide behind a common cause

In “An Affirmative Action Empire: The Soviet Union as the Highest form of Imperialism” the author brings up the conflict that Lenin and Stalin saw with Nationalism. In

Moreover, I think it is important to discuss who decides that a nation will follow in a certain Nationalism ideology? Furthermore, is Nationalism fluid- can you go most of your life believing you are Austrian- Hungarian, only to be told later in your life you are German? How does that change your allegiance to your nation and government?