I was extremely interested by the depiction of Soviet society in this movie. This film, set in late 1920s Russia, seemed to reflect the theme of the old, Tsarist ruling class pitifully struggling to remain relevant while a new proletarian society emerges around them. The main plot if the movie revolves around representatives of the nobility and clergy scrambling to find some old jewels hidden in a chair, a quest that (spoiler alert) ultimately turns out to be in vain. While these metaphors for the Tsarist ruling classes are searching for their old wealth, we can see the signs of the old society dying and a new one rising around them. The death of the old order can be seen in things like the terrified meeting of old Russian officials and the auctions selling off their stuff. Meanwhile, the Soviet society is starting to emerge around them, as seen in the Red Army troops marching and singing, the public lectures, choirs, propaganda posters, and just a general sense of camaraderie among the people. With all that in mind, I’d like to pose the question: what message does the film want us to take from this? Do they think the fading of the old order is a good or bad thing?

Twelve Chairs

Going into watching this film, I was not sure what to expect. In the opening scene when Bender pretends to be a Soviet official to get stuff from a store clerk, I was not quite sure where this film was going to go. Would it be a movie presenting order? A drama? A comedy? And although it was the latter, I was still surprised that this sort of comedy was allowed in the Soviet Union. Twelve Chairs is a very light hearted movie, yet there seem to be some clear criticisms of the Soviet Union within the plot. Such is the fact that Ippolit Vorobyaninov is even looking for the chairs in the first place. He was essentially demoted, and this fortune could be a chance to reconcile that. Moreover, the priest seems pretty corrupt. I found it to be confusing that the Soviet Union would allow a movie to exist that seems to lampoon failings in their government. However, is that maybe the point? To poke fun at the instability after the war? As this film acts as a look back into a different time, is there seperation between this story and the 1970s?

Twelve Chairs Film

This film from the very beginning is a very accurate representation of soviet culture the setting of the film is just incredible. I love how the man, in the beginning, used his what I’m assuming pretended to use a officials red card top bribe a shop owner to give him food and goods, in exchange to not report him to USSR for violations. This film is very rich and full of stuff we talk about, for example at 52:39 the auction for the mother-law of “Ippolit Matveyevich” who is known in the movie for being the Marshal of Nobility. The Soviet auctioneers addressed the mother-in-laws furniture as not earned and rather that was owned by the corrupt aristocracy. This is related to our discussion from the Russian Empire transitioning into the Soviet Union and how the regime looked at the old republic. Everything in this film exemplifies everything we have been discussing and find it very easy to connect with. Also, this film allows me to visually see what we have been talking about, which I think is very important to paint that picture within our minds. To Conclude, the only thing I would like to discuss is the adaptations between the old film and this rather newer film. What was altered and changed from both of them?

Soviet Humor: By the People, For the Elites, and Censored by the Officialdom

After reading chapters 3 and 4 from “Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge” by Mayhill C. Fowler, it is easy for me to presume that we all saw the issue of Soviet censorship from a mile away. Although, with the idea of not having to entertain an audience of “normal” people and rather one in which supplies funding for the theater directly, it is not a wonder why the content of the performances was catered to them instead. However, Fowler points out, “according to Soviet ideology, shouldn’t all art be for everyone? After all, too much focus on securing the hard-won rubles from the lower-class audience members created art that was ostensibly ‘lower’ in the artistic hierarchy of the Russian Empire” (Fowler, 96). I feel this is an interesting concept and obviously counterintuitive to spreading culture when, in reality, only the elites enjoy the larger productions in Moscow.

Perhaps the real culture is to be found in that of the literature discussed between the comparisons of Ostap Vyshnia and Il’f -Petrov. Both were very famous and responsible for works that are still referenced as great sources of Soviet literature. Although Vyshnia struggled with the issue of making his work something for the masses to enjoy, he had no struggle in creating well praised Soviet entertainment. I believe that besides the modernized level of production, Soviet Ukrainian culture was most noteworthy for the simple fact that the Officialdom supported and promoted it in a way that we have yet to see so far. This idea is supported by Fowler’s statement that “Indeed the years of Ukrainization corresponded to years of artistic flourishing in Soviet Ukraine” (Fowler, 118).

Soviet Influence

I think that it is extremely smart and well done by the Soviet Union to come in and support artistic movement when it is needed most. Artists needed to have their business’s survive and that even meant making a deal with the devil himself. I just am curious as to what everyone else thinks , whether this deal really excludes other cultures practices in the work of art. could this not be fair economically for the creators of the work of art in this new economy? “In the heady days of the New Economic Policy, artists competed for funding from various pots, whether from Party or state committees at the city, republic, or Union level, or from the Arts Workers’ Union. But, by the late 1920s, artists had achieved what they had long desired: full state support for the arts. As artists had imagined, state support facilitated artistic production.” Page 97

MLA (Modern Language Assoc.)

Fowler, Mayhill C. Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge : State and Stage in Soviet Ukraine. University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division, 2017.

APA (American Psychological Assoc.)

Fowler, M. C. (2017). Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge : State and Stage in Soviet Ukraine. University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division.

The Role of Art and Soviet Influence

In Chapters 3 and 4, Fowler took a deeper dive into the Soviet government’s control on art and how this focus affected various forms of entertainment. Last class we discussed censorship, but I think it is important to think more about how censorship and manipulation of the arts and media can alter the perception of citizens and how the need to be funded by the state affected the execution of the arts. The text states, “Artists could not depend on book or ticket sales to prove resonance with an audience. Competition among artists for financial support was still fierce, but artists focused not on soliciting interest from the audience members or private patrons, but rather from the Party-state” (Fowler 96) and “With audience input therefore removed, Party-state patronage became crucial to finance theatre, and local connections with officialdom provided the path to securing funds. Socialist theatre had no box office – or at least not a box office contributing in any significant way to a theatre’s income. What mattered for success was not how many tickets a theatre sold, but how many seats its managers succeeded in “organizing” through Party connections” (116). I never thought about just how far the Soviet government financed and influenced art, especially theater, across the various nations.

Questions I’ve been thinking about:

- Do you think catering the message of the arts to benefit the Soviet ideals compromises the purpose of theater, film, literature, etc.?

- On page 113, the author discusses the statistics and number of people who actually visited the Berezil, which turned out to be only about half a percent of the population in Soviet Ukraine, and also states that an even smaller percentage saw Hello from Radiowave 477!. Even with such recorded low audiences in comparison to the overall population, do you think shows and programs like this were influential to developing Soviet Ukrainian art? Were they successful?

- In the last ten pages or so pages of Chapter 3, the author discusses the nationality policy’s affect on the arts, specifically referring to Soviet Ukraine. How did the nationality policy actually hinder minority art and create an ethnic hierarchy?

- Despite the flourishing of art and the representation of various ethnic identities, the founding fathers of art and theater in the Soviet Union all met tragic endings and their legacies were not always discussed positively. The text states, “In 1937 Khvyl’ovyi had committed suicide, Dosvitnyi, Kulish, Iohansen, and Kurbas were shot, and Hirniak and Vyshnia were imprisoned in the gulag” (Fowler 118). Do you think the art movement was still successful in promoting innovation and promoting diverse ethnic identities?

Policy to Theatre Scenes Comparison

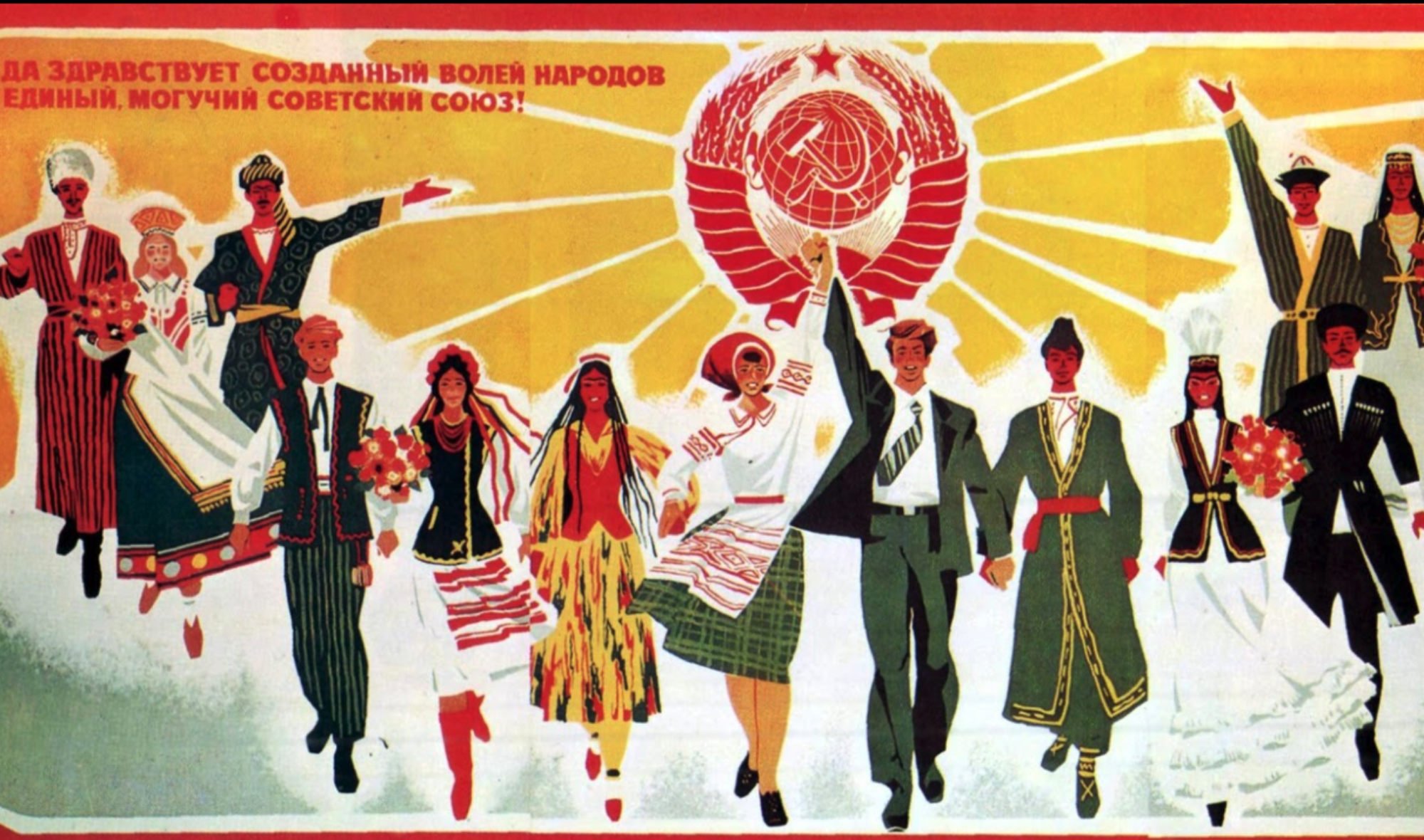

“There is a famous scene, in fact, in Circus where the small mixed-race child … is passed around the entire audience of the circus, and everyone sings to the child a lullaby in a different language of he Union” (98).

“The literary fair solved this dilemma, like good Soviets, by organizing the arts according to ethno-national categories: Jewish audiences were assigned to the Jewish theatre with Jewish artists and Jewish plays; Ukrainian audiences to the Ukrainian theatre…”(119).

Reading through the third chapter of Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge: State and Stage in Soviet Ukraine I found this two passages to be in conflict with each other (go figure, right!). I was wondering what the class thinks? Is this another case of financials determining the agenda or are cultural boundaries more pronounced than officials thought? Moreover, what do you think about the cultural exchanges discussed in the very first part of this chapter?

To be or not to be? Not to be

As we have progressed chronologically in Soviet history we have been encountering more direct examples of communist repression and persecution. Encountering things identifying as ‘great’ but were far from it such as the Great Famine, Purge, and Terror. Apart of the odious apparatus of Soviet persecution was the collectivization campaign of course, and in the reading we discern that this had a cultural aspect of it with the suppression of the avant garde Ukrainian art movement. In these chapters we are described the formation of a distinct cultural epicenter in Soviet Ukraine. This was due to the unique cultural landscape of the region, being made up of Jews, Poles, Russians, and Ukrainians. Investments in the imperial Southwest by Catherine the Great into the humanities of Odessa created a burgeoning artistic center. “But Odesa, in fact, belongs to a greater cultural phenomenon of the entire region. Multi-ethnic interactions in the small towns and cities throughout the southwestern provinces inspired and shaped the many artists featured in this book” (Fowler 29) This hub of cultural in Soviet periphery provided a different type of artistry than that offered in Moscow due to cultural differences in the region. As with most other situations that we have evaluated in the Soviet Union this group will suppressed in the name of party and state interests so it leads me to the questions of,

How was Ukraine’s diversity a blessing and a curse? How does multilinguality of the art from the region affect how Soviets should perceive it?Do ethnically diverse metropolitan regions intrinsically pose a threat to authoritarian rule?Do these artists by the nature of them not being outlets of the state therefore present a threat to Soviet national security? Or is state funded and controlled propaganda the only art that can coalesce to party interests? Specifically in relation to the Stalinist Soviet state.

Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge: State and Stage in Soviet Ukraine, The Literary Fair

Todays reading, seemed to follow a theme we’ve come to be familiar with in this course: creating a new society. It is very clear week after week that the Soviet officials are acting as entrepreneurs to create and market a new way of living. And no nation or group of nations can be complete without culture. Culture is such as affective way to instill pride and community within a group of peoples. Moreover, a cultured area of culture, the arts, have been used since the Paleolithic period. Just as it would be in any Soviet territory, the arts are used very tactically, as a tool. Mayhill Fowler states, “The arts were there-fore not a luxury, but rather a central component of the Soviet project. Consequently the state created, managed, and financially supported newspapers, journals, and arts institutions, all of which offered jobs for artists” (Fowler 58). The Soviet Union played patron to the arts to support artists in which ever media they create, however, it would not be the Soviet Union without some kinks due to hasty action. Moreover, it seems that a lot of artists in and coming out of the civil war were prolific in creating in a very close knit art scene, and many began to travel to the seemingly new artistic hub, Moscow. Specifically Mikhail Bulgakov lived in a new time where the arts had a significant place in society, and the government was funding their lives and careers. However, the art scene in Soviet Ukraine differed in significant ways, “First of all, many of the artists in Soviet Ukraine were also officials. As such, they invested as much in the creation of a new state as in the creation of a new culture” (Fowler 62). These two worlds of art existed at the same time and within the same “nation”, yet were influenced so differently.

- How do the signifigant differences between artists in Moscow and Ukraine change the way in which we could see their art? How do their positions before and after the war effect the art and culture of the new societies?

- Are the actions of Soviet Ukraine possibly treating to the doctrine of the Soviet Union? Does Soviet Ukraine do things better than the SU regarding cultural action and thought?

- How does the Literary Fair support or reject the new society the SU is trying to create?

- What is the significance of the close relationship the military has with the arts?

Is it worth the effort?

Going into this reading, I am sure we were all probably not surprised to find out how heavily involved the Soviet government was in theatre. We’ve already seen countless examples of government officials meddling in cultural practices. On page 83, Fowler says, “The GPU was actively involved in culture not only to suppress but also create a Soviet artistic culture.” In this chapter, we see the great lengths the Soviets go to suppress bad culture and create their own, but was it worth it from a Soviet perspective to pour all these resources into censoring theatre (or anything else related)? Personally, I’ll say yes since theatre can have such a profound impact on society. When it is good enough, people start to really discuss the contents. What does everyone else think?