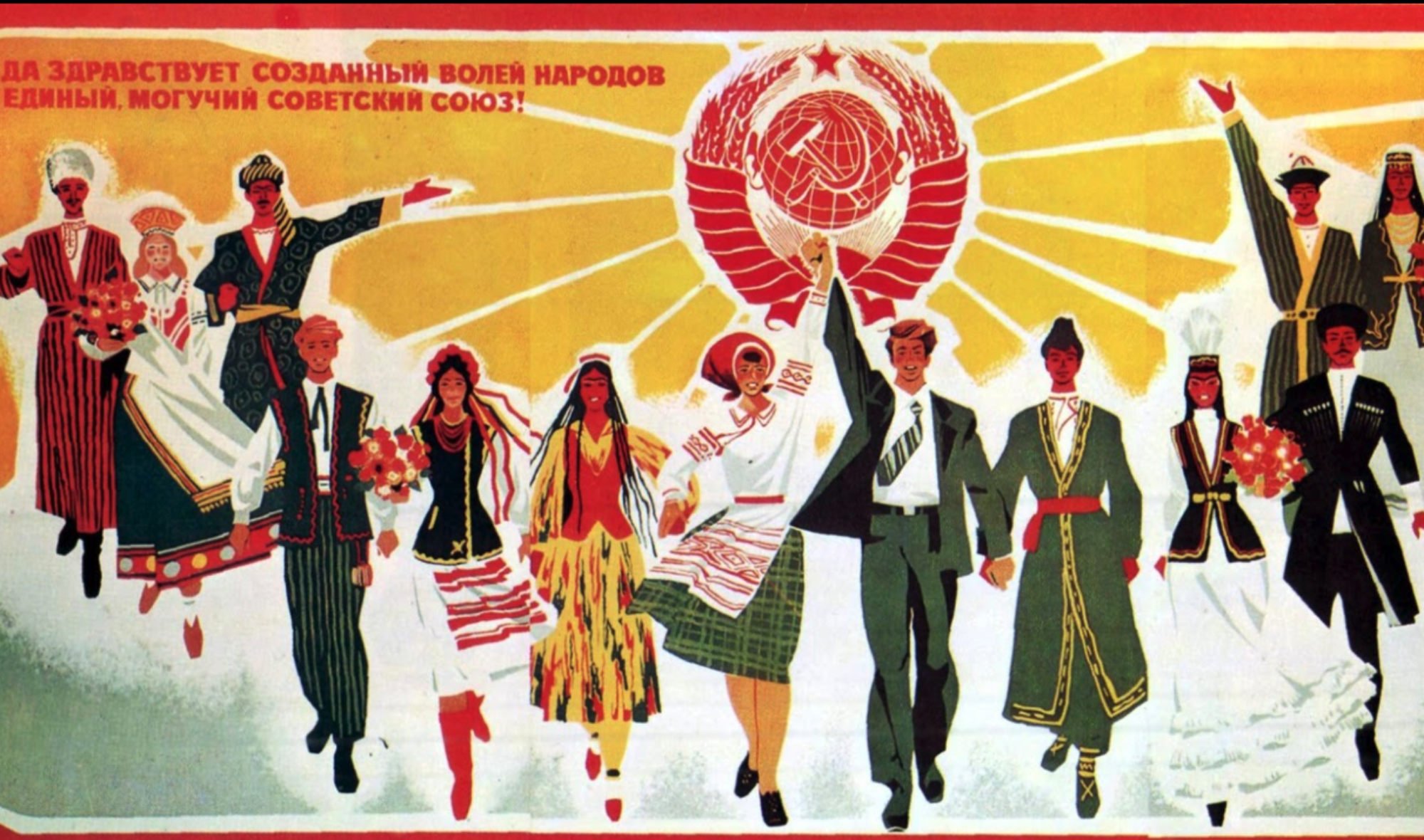

As I was reading through Chapter 8, the creation of the racial hierarchies within Germany’s newly conquered lands made me think about Soviet efforts in the same place. We have talked the last few classes about the Soviet Union’s struggle to organize people in the borderlands (and throughout the Soviet Union) based on nationality. When the Germans take control, it seems as though they are doing something similar, but on a much more complex level. Although the Germans face some challenges, they seem to be much more organized with the way they undertake this huge project. I do not want to say they are successful in achieving their goals, but it seems they get closer than the Soviet government. Is this because the Soviet’s are strictly looking at things from a primarily economic view? Obviously the Germans are more concerned about actually separating (or eliminating) certain groups. Hope this post makes some sort of sense.

The Great Purges and Power Vacuums

The purges were a horrible period in the Soviet Union, which caused the deaths and exiling of thousands of people who were more than likely to be innocent of any “crime against the state” or espionage. However, many people were able to take advantage of this situation as well. A prime example would be Leplevsky, who spread rumors and half-truths about Balytyski that eventually got him exiled and killed. When Leplevsky came into power at the NKVD, he arrested all of Balytyskis leading deputies and replaced them with young workers who would follow him blindly (pg 157). Under his power, almost 20,000 people were arrested in connection to a “polish conspiracy”. Some of these people included top party leaders who had otherwise good names among the people.

Given what we know about the purges and how they worked, do you think that it was inevitable that people like Leplevsky would come into power and abuse the state of the Union?

From Bad to Worse: Stalinist Policy in the Kresy to 1935

Reading through chapters 3-5 of “A Bureaucracy of No Place”, it quickly becomes clear to the reader that the Soviet bureaucracy’s handling of the Kresy zone was wildly inconsistent and seemed to have only made things worse with every measure it took. Economically, the issues started with the New Economic Plan, where (among other issues) peasants found that they were having an immense amount of difficulty producing enough crops to support themselves. The economic issues were further compounded by the Soviet crash implementation of mass collectivization, which produced an immense amount of pressure on the peasants. Conditions got so bad that this region eventually went into a state of open revolt against the Soviet government. The fallout from this debacle earned the Soviet authorities the resentment of many of the border peoples, which they responded to initially by imprisoning many suspected “nationalists” and “foreign agents” before settling on the mass deportation of ethnic Poles and Germans to other parts of the Soviet Union.

What really struck me while reading this section of the book was simply how inconsistent and uncoordinated the Soviet administration was during this episode. This can be seen in instances such as the logistical difficulties Zborovskii faced while overseeing the deportations, which were the result of poor upper level communication and administration. One other particularly bizarre example was a section of the main Soviet Presidium declaring the scattered Polish cultural measures a rousing success and ordering more teachers into the Kresy. The situation became even stranger when 40% of those teachers were arrested by the Ukrainian NKVD on charges of “nationalist activity”.

All in all, this whole affair was a debacle for the Soviet government, and is an accurate reflection of the atmosphere of paranoia and inconsistency that dominated Soviet thinking during this time.

Agriculture, Collectivization, and the Great Leap

The Soviet administration inherited one of the most defunct political systems in Europe. Historically the areas that constituted the USSR were mostly poor and unindustrialized except some metropolitan areas and just emerged from war and pestilence while still suffering widespread famine. The public administration overhaul required was obnoxiously large and the Soviets leadership made substantial adjustment but the implementation of these policies was barbaric and coercive. The necessity of vast agricultural reform was apparent to Soviet leadership, the proletariat was starving and the infrastructure required to feed them did not exist, not to mention the rampant poverty in the border lands

“No matter how hard I work, I can’t better myself”

. The odious apparatus the Union used to fix this was collectivized farming which created more problems than it solved. The absolute brutality the Soviets inflicted on Kulaks in the name of efficiency highlighted the key problem about conceptualization to actually enacting policy that the Soviets struggled with.

Village Reactions to Deportation

It is clear in chapters 3-5 in Biography of No Place that deportation was a chaotic and poorly planned event. Not enough resources were given to the villagers who were moving, nor were enough resources given to the people moving them so that they could have a safe journey. In fact, in the chapter “A Diary of Deportation”, Zborovskii mentions that there were not enough wagons to carry the elderly and the children to the resettlement areas. Some placed did not even have enough paper for him to write on. However, this did not seem to affect some of the villager’s outlooks on deportation. In fact, some villagers were happy to be sent to these new areas.

“18 February 1935: In the [German] village of Negeim I called a meeting of the Young Communist League at 10:00 a.m. to get their participation in the campaign. They broke into four brigades. We informed the families concerned…about90% were happy to be going. For instance, Gustav Ryk said, “I am happy about the resettlement. It will be a lot better in the new place. They have good black earth there.”

Some villages, though, were upset or confused about why they were being deported. One townsperson said it was because they were trying to get rid of Polish and German residents. Others believed it to be a punishment for refusing to do collective farming. Why do you think that some villages were happy to move, while others weren’t? What could have convinced them that this was a good move?

A Biography of No Place: The Numbers Don’t Lie?

Blake Aber

In A Biography of No

A Biography of No Place

I find it interesting on what inhabitants were to do in the Kresy region and as well as other borderland boundaries. With the establishment of the Marchlevsk Polish autonomous Region, Pulin German Autonomous Region, as well as the hundred of other Jewish, Polish and German regions. Whereas the other inhabitants in these are at a disadvantage because their nationality was not recognized in the eyes of the Soviet Union. For the other inhabitants in these regions to speak their native languages and even take control of their schools, courts, libraries and establish their own communities, the Soviet party made them take the ultimate sacrifice to change their own identity. (Page 9 Lines 4-8) This is so problamatic because, these people carried the distinct traditional and local nationality concept. In addition, I feel that this topic is very important to our discussion lately and believe we can expand on this topic in class.

So I pose the question as to whether or not the transformation of the nationality for these people actually hurt the Soviet Union by not making these people want to become stalinist or even make them into revolutionists against the regime? Furthermore ,did the inhabitants within these regions see no other choice but to change their identity to benefit themselves or capitulate to the Soviet Union?

Villagers and the Soviet Government

In the second chapter of “A Biography of No Place”, Kate Brown discusses the “threat” posed to the Soviet Union by villages and towns in the countryside. These threats include the lack of revolutionary attitudes from villagers. Brown states that this could be attributed to their ignorance of “borders, ethnicity, class, and political mood” that the Soviet Union was trying to impose upon them from hundreds of miles away. She goes on to say that these things barely existed in the daily lives of villagers who were still living their lives based on their own holidays, schedules, and religions. These “threats” caused Soviet leadership to take drastic measures, such as deportation, out on these people. Why were they so threatening to the Soviet government? What was the issue with people practicing their own culture, even though Lenin had stated in earlier speeches that they encouraged these practices?

Lenin’s Vision

Although it is really short, Lenin’s speech at the All-Russian Navy Congress really provides a window into how the Soviets will handle the all important question of culture that we started discussing last week. The date the speech was delivered, December 5, 1917, is something we should keep in mind in our discussion of the speech. This is just months after the October Revolution. At this point, I think it is safe to say Lenin had to be extremely careful to say the right things, even if that meant there had to be some compromise with his actual views. This speech spreads a message of unity while also still seemingly acknowledging unique cultures (ie Ukraine). So here is where my question comes in: In the speech Lenin says, “We are told that Russia will be divided, will split into separate republics. We should not be afraid of this. No matter how many separate republics are created we shall not be frightened by it. It is not the state frontiers that count with us but a union of toilers of all nations ready to fight the bourgeoisie of any nation.” Do you buy this? Is it possible to unify to “fight the bourgeoisie” without erasing some (or all) cultural elements that are not “Soviet” (when that becomes a thing)? Does Stalin’s speech contain a more thorough plan to carry out what Lenin is promoting, or is it something different?

Stalin & the Toilers

Out of all three of the readings I found Stalin’s speech, “The Political Tasks of the University of the Peoples of the East”, the most interesting. Stalin partially stylized the speech to assume the role of a “how to” manual on how to become part of the revolution and why certain countries are still under the grip of capitalism. Instantly he establishes an East vs West argument, the East where the Bourgeoisie no longer exist and who are free from colonial countries, and the West who still participate in capitalism and who allow the elitist Bourgeoisie to rule. I think his five step plan to incite revolutions in capitalist societies are interesting, with almost every aspect concerned with bolstering the Proletariats and keeping their best interest at heart (rather than the Bourgeoisie).

Two questions: What/who are the Toilers? Do you buy Stalin’s ideas on Model Republics?